Gestational hypertension is a common hypertensive disorder that occurs exclusively during pregnancy. It is characterized by the new onset of elevated blood pressure after 20 weeks of gestation in women who previously had normal blood pressure levels. This condition is a significant concern in obstetric care because it can affect both maternal and fetal health, and its management requires careful monitoring and timely intervention to prevent complications. Understanding gestational hypertension involves examining its definition, diagnostic criteria, differentiation from other hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, management strategies, and long-term implications for maternal health.

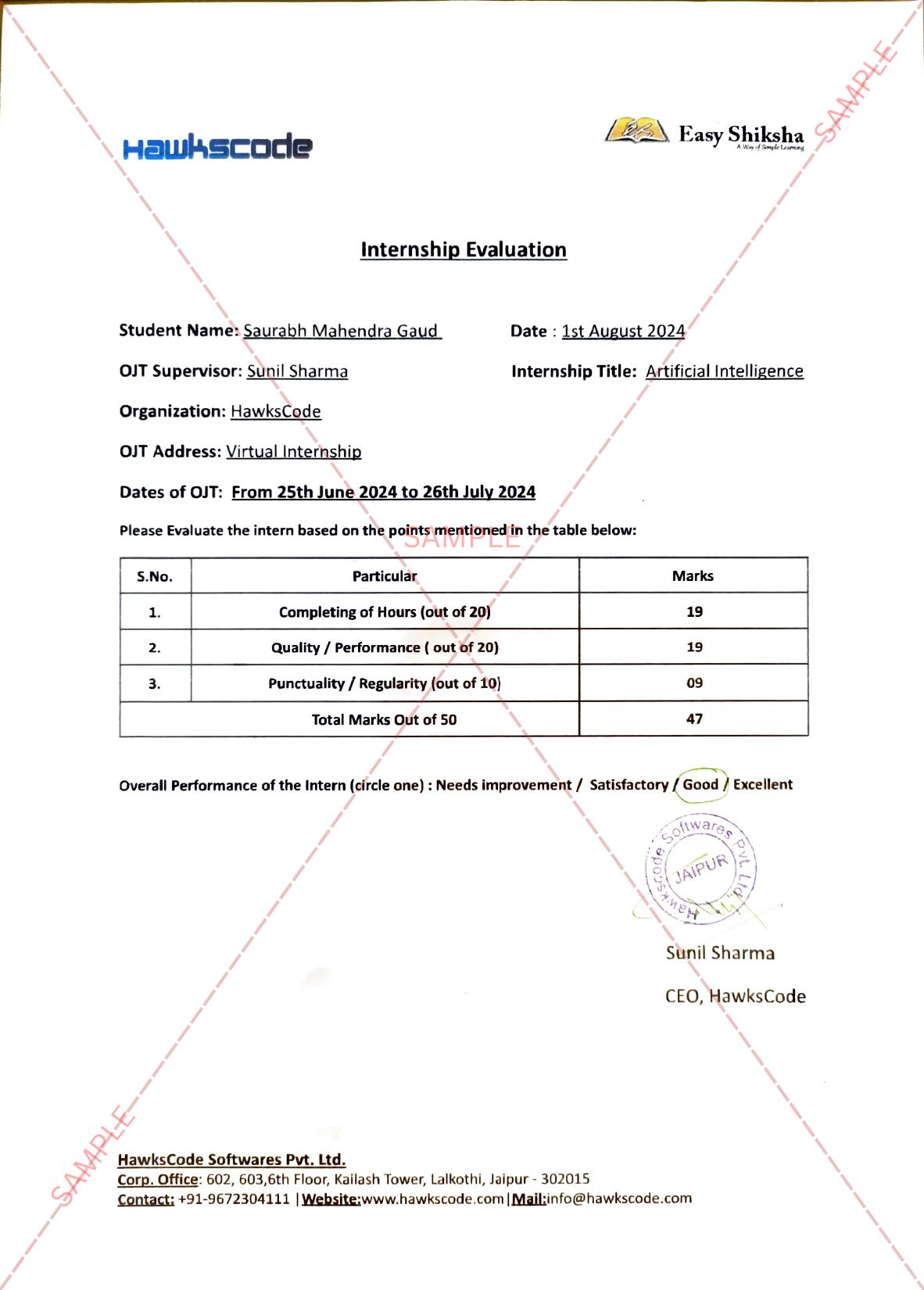

Definition and Diagnostic Criteria

Gestational hypertension is defined by the appearance of elevated blood pressure measurements—specifically, systolic blood pressure greater than 140 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure greater than 90 mmHg—after the 20th week of pregnancy. A key feature distinguishing it from other hypertensive disorders is the absence of significant proteinuria, which is typically less than 300 mg of protein in a 24-hour urine collection or an equivalent amount in spot urine testing. Additionally, unlike preeclampsia, gestational hypertension should not be accompanied by signs of end-organ dysfunction, such as abnormal liver enzymes, low platelet count, or kidney impairment.

The diagnosis is confirmed postpartum if the elevated blood pressure resolves within 12 weeks after delivery, and there are no signs of preeclampsia or other organ damage. This postpartum resolution is important to differentiate gestational hypertension from chronic hypertension, which is present before pregnancy or diagnosed before 20 weeks of gestation.

ALSO READ: Rumour-around-the-closure-of-offline-classes-amidst-the-increasing

Classification of Hypertensive Disorders in Pregnancy

Gestational hypertension is one of four major hypertensive disorders that can affect pregnant women, each with distinct clinical features:

Preeclampsia – characterized by hypertension and proteinuria or signs of organ dysfunction, such as liver or kidney involvement.

Gestational hypertension – new-onset hypertension without significant proteinuria or systemic symptoms.

Chronic hypertension – pre-existing hypertension diagnosed before pregnancy or before 20 weeks gestation.

Preeclampsia superimposed on chronic hypertension – when preeclampsia develops in women with pre-existing hypertension.

Accurate differentiation among these conditions is crucial because it influences management decisions, including timing of delivery, need for medications, and surveillance strategies.

Clinical Evaluation and Differential Diagnosis

The initial evaluation of gestational hypertension involves a comprehensive clinical assessment. Accurate blood pressure measurement is essential, ideally using validated devices and proper technique. Healthcare providers also consider and exclude white coat hypertension—elevated blood pressure readings due to anxiety or stress in clinical settings. By confirming persistently elevated readings with repeated measurements or ambulatory blood pressure monitoring.

Patients are questioned about symptoms associated with preeclampsia, such as headaches, visual disturbances, epigastric pain, or swelling. Laboratory evaluations include measuring urine protein excretion, platelet count, liver enzyme levels, and serum creatinine to rule out preeclampsia or other secondary causes like glomerulonephritis, thrombotic microangiopathies, or endocrine disorders.

Distinguishing gestational hypertension from chronic hypertension or secondary causes is critical because management strategies and prognosis differ significantly.

Progression and Management

Research indicates that between 10% and 50% of women diagnosed with gestational hypertension may progress to preeclampsia, especially if diagnosed early in pregnancy (before 34 weeks) or if blood pressures are particularly high. This progression underscores the importance of vigilant monitoring and timely intervention.

Management depends on the severity of hypertension:

Severe hypertension (blood pressure >160/110 mmHg) requires immediate hospitalization and often delivery, similar to preeclampsia with severe features. This reduces the risk of maternal complications such as stroke or organ damage.

Doctors can often manage non-severe gestational hypertension on an outpatient basis, regularly monitoring blood pressure and laboratory parameters, including urine protein-to-creatinine ratio, platelet count, serum creatinine, and liver enzymes. Patients are educated about symptoms of preeclampsia and advised to avoid strenuous activities, although bed rest is not routinely recommended.

Antihypertensive medications are reserved for cases where blood pressure remains high or increases rapidly. Common antihypertensives include labetalol, nifedipine, and methyldopa. Doctors monitor fetal well-being through non-stress tests (NST), biophysical profiles (BPP), and ultrasounds to assess growth and amniotic fluid levels.

Timing of Delivery and Postpartum Course

The goal is to deliver at term (37–39 weeks) whenever feasible, depending on maternal and fetal status. If blood pressure remains uncontrolled or complications arise, earlier delivery might be necessary. Postpartum, blood pressure typically normalizes within 12 weeks. However, women with gestational hypertension are at increased risk for developing chronic hypertension and cardiovascular disease later in life.

Long-term Implications and Recurrence Risks

While most cases resolve postpartum, researchers associate gestational hypertension with increased long-term maternal health risks, including hypertension, ischemic heart disease, and stroke. Women who experience gestational hypertension have a higher likelihood of recurrence in future pregnancies. Low-dose aspirin prophylaxis, started early in pregnancy, can mitigate this risk.

Perinatal Outcomes

In cases of non-severe gestational hypertension, perinatal outcomes are generally favorable. With low rates of preterm birth and fetal growth restriction. However, severe hypertension increases the risk of adverse outcomes such as preterm delivery, small-for-gestational-age infants, and placental abruption. Online Courses with Certification

Online Courses with Certification

Summary

In conclusion, gestational hypertension is a prevalent hypertensive disorder. That occurs after 20 weeks of pregnancy without significant proteinuria or organ damage. It requires careful diagnosis, vigilant monitoring, and appropriate management to prevent maternal and fetal complications. Most women recover fully postpartum, but the condition has significant implications for long-term health. Early identification and management are essential to optimize outcomes for both mother and baby. Making gestational hypertension a critical focus in prenatal care.

Dr. Hira Mardi

Senior Consultant – Obstetrics & Gynaecology and Fertility Specialist

Kinder women’s hospital and fertility center

Bangalore

For information related to technology,visit: HawksCode and EasyShiksha